Today was the day for in-depth discussion, which is good because I was having trouble deciphering everything I was feeling. Today some of us met in the Rūnanga Room at uni for a ‘Teach In’ hosted by our lecturer, Whaea Linda Tuhiwai Smith.

We came to share space. Free space. Safe space. Space where we could share how we felt. Space where we could sit and listen. Space where we knew we weren’t under a microscope. Space where we could vent. Space where we could share trauma, whether it be emotional, generational, historical or any other. Space where we knew our voice would be heard. A.1.01, the Rūnanga Room was that space today, and I’m grateful to have been given the opportunity to be a part of discussions. Although, to be honest, I wasn’t sure exactly how ideas would fall from my grey matter.

On Friday 15 March, 2019, at gunman was greeted at the door of Mosque Al-Noor with, “Greetings brother”. That gunman then turned his firearm on and murdered that man, and 49 other innocent men, women and children in an act of absolute, cowardice, hate-filled, humanless, heartless terrorism.

That thing (I refuse to say his name) stole the lives of hardworking, good and loyal parents, and stole the lives of our next generation of New Zealanders, on one of the Muslim faiths most significant days, Jumu’ah, or Congregational Prayer.

That word, “prayer” gives insight, I think, into what type of mindset this thing is in. To massacre, commit murder, upon those who are in prayer, in their place of worship, in their whare karakia, their marae, means this act was one of nothing but hate. It also means, that any culture he saw as being on his “Fuck You Coloured Cunts” list could easily have been next, and the question I found myself asking a couple of days ago was, “If it wasn’t the Muslim faith he targeted first … which culture would he have targeted instead?”

Random thoughts:

You prick. Your actions have instilled fear and discourse that re-immerses us back into the pool of trauma we already tread water in.

How dare you reawaken this in us! What have our cultures EVER done to you!?! What has ISLAM ever done to you!?!

From microaggression to massacre. There should be no room for light to shine through that darkness.

But light always finds a way to shine through.

The talks today were fog clearing. Insightful. Painful. Helpful. Traumatic. Heavy.

They were good. Good in the way that they allowed people to speak freely, and clear their own minds. Share their thoughts. Share their stories. I was whakamā to share what I had been doing last Friday because I had been … having fun … watching my babies perform on stage after they and their kapa brother’s had worked their bums off practicing for Polyfest. I was ashamed to approach it until Whaea said it was important not to feel guilt for doing whatever you were doing that day, because we were all leading our own lives prior to the terrorist attack – there should be no guilt in living your life. There should be no guilt in celebrating achievements. Their should be no guilt in normality. But while I was with ‘my kids’ (the entire kapa is packed with ‘my kids’ – 30+ young men who attend Titikōpuke Kapahaka, from Dilworth School in Auckland) I saw their extreme guilt in receiving awards while ‘just down the road’ their fellow countrymen were grieving the loss of their loved ones. The boys felt guilty for celebrating their achievements until the were told the exact same thing, “I know you’re feeling empathy for the loss of those in Christchurch. I know some of you have family in Christchurch. But keep yourself here. In this time. Our time. Don’t feel guilty for something that was in no way, your fault, or in your control. Stay in the kaupapa. Be proud of your achievements. Celebrate them.”

Out of all the kōrero, a few things that stuck out in my mind:

- Everyone in the room had suffered, or was in the process of recognising, their own trauma

- Everyone in the room had experienced some, thing, some narrative, some action, discourse, pertaining to their own lives or of those they are close to that had been triggered and had come to the surface via this act of terrorism

- No matter how big or how small, everyone’s stories were important and every story was cherished

- Our narratives, our histories as Tangata Whenua are still being ignored and will continue to be so until WE make change

- Those who have lived in and were raised in and around Christchurch had very similar narratives of trauma, yet each person lived completely different lives. It was hearing their histories that hurt the most, because their histories will never be the stories of the rest of the nation … I will, for example, never know what it is like to live in a city where being targeted by skinheads and other alt-right groups, because of my race and/or gender, is so normal that only brown people talk about it – because I’ve only ever heard brown people talk about it … because europeans don’t get targeted by gangs like that. And some of them never want to listen to what they believe doesn’t exist. It’s half the reason why the facebook frame’s saying, “This is not us” piss me off. They were designed by people who either ‘don’t see colour’ or who ‘didn’t realise there was a problem’. Bull. You frikkin see it alright. I have a lifetime of historical and generational trauma that calls you out on it, and I refuse to get over it until you start acknowledging your part in it.

- ‘Godzone’. Gods’ own. New Zealand. Is completely f’d up.

How does talk of Māori historical trauma bind with this kaupapa of terrorism. Simply put, there is a piece of me that feels we as Māori, as tangata whenua, as mana whenua, have been forgotten. “Law and policy makers don’t know what to do with Māori, as a race, when they make policies, because if they acknowledge us as tangata whenua they then have to acknowledge us as part and parcel of the policy making process – and they don’t want to give us tooooo much power, do they?”

True. We might actually save the whales, the Kauri, the international animal endangered list, find alternative, clean, green renewable power sources, increase our education track record, lower our prison one, stop addiction in all its’ forms, solve world hunger and poverty and basically be better off. Nah, screw that, keep Māori out of the policy making processes. Ignore us. There we go – now we’re one. Yaaay!

There is more to it than that though. The attack on these masjid have brought the pus to the tops of our wounds that have never really been allowed to heal. None of us, as minorities in New Zealand (meaning Muslim, Māori, Asian, Pacific Islander etc etc), are safe from any kind of terrorism. Our skin colour and culture is the flame to which all bugs are drawn to, good and bad – the only difference is it’s the bad bugs that hang around and make life difficult. Our Muslim brother’s and sister’s are a strong community, and once they have been given time to grieve and practice their tikanga, they will find their own small steps back to ‘normal’ life – but, life in New Zealand for them will forever be one where they thought they were coming to a land rich in culture (whatever the hell that means). A land full of opportunity, and a chance at a peaceful life to raise their children in a country that doesn’t know anything of war. Those 50 men, women and children didn’t deserve this.

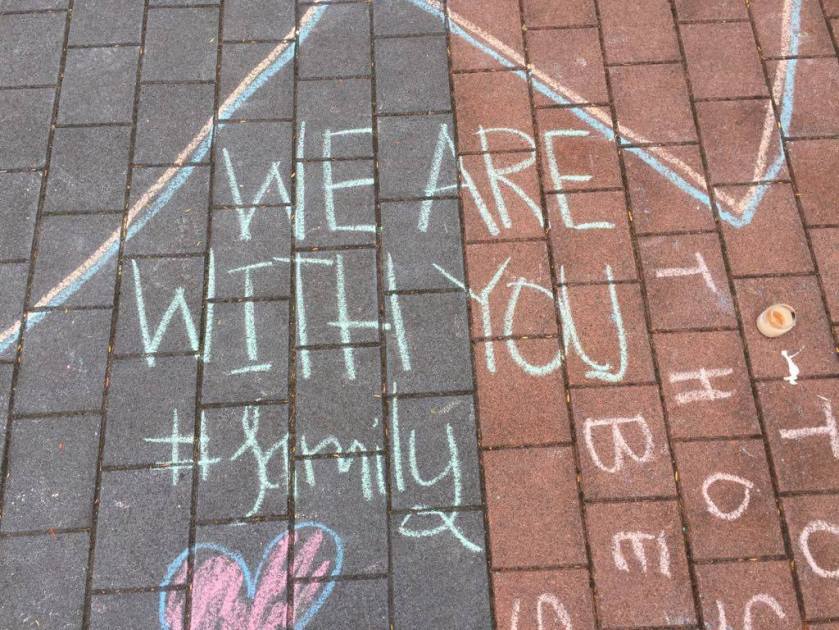

The images I took today, which are shown in this post, are part and parcel of the love and devotion the wider student body is showing for our Muslim community. The outpouring of aroha and solidarity has been phenomenal for our Muslim brother’s and sister’s.

Our VC stood in front of the wider student body at an event that was very well organised by the Waikato Muslim Students’ Association today. He stood and gave his very well practiced speech, which shows he’s a business man, and not an off the cuff sort of guy – nothing wrong with that though. I’m a planner as well. Hell, even Jacinda is a planner.

He stood in front of the wider student body, giving his heartfelt condolences and love on behalf of the university, and, somewhere along the way, wording similar to, ‘This is the first massacre New Zealand has ever experienced’, fell out of his face. There were staff members there who literally felt their jaws drop to the ground at that statement. Students I spoke to after class this afternoon each baulked, turned to their friends and said,

“Did that m’fer just say this is the first massacre NZ’s ever experienced?”,

“Wait, what did he just say? Did he just say that Rangiaowhia didn’t matter? What, so Pukehinahina didn’t matter either? Ohhh I get it. It’s not a pākehā thing, so it doesn’t matter. Gotcha (snaps)”,

“Hoooooly shit. He’s just discounted our whole fucking history in front of the student body … good one, his dumb ass has just made it ok for the rest of the uni to think it’s ok to ignore our histories too”

“I thought, far what a rat shit fulla, I know he thinks we’re shit, otherwise he wouldn’t be thinking of stripping FMIS of its’ faculty, but that was pretty low eh, making out our narratives don’t exist”

Good one VC. Way to ignore a whole culture’s past. Whether they happen 175 years ago, 75 years ago, or 5 years ago, those massacre’s happened. Our nation’s history is dotted with stories of massacre’s from a colonial viewpoint – ‘victor’s justice’ – so I get why our histories don’t register with him, because they wouldn’t matter unless they were from the viewpoint of the victor.

How else does this come from the original kaupapa of terrorism?

There are Pākehā in our community who actively seek to address, take responsibility for and heal the wrongs of their own community, family and race. I know many but a friend of mine in particular, who comes to my Māori302 class, has had some trouble peeling back the layers she feels. I see it in her eyes when we pass each other in the halls, I hear it in her voice when we stop to talk to one another. She has told me that her look into Te Ao Māori began with the disgust she felt at her brother for the way he talks about Māori and Pacific Islanders. She calls her family a bunch of racists, and I know sometimes she feels out on the edge of her circle of influence. She calls her brother out at every opportunity, but her journey would have had to start with the fear that she was going against the grain, not ‘being normal’. It’s people like her, and many others, who are trying to take this burden on for their entire race. These people need to be supported as well and reminded that their job isn’t to feel for their race, it’s to feel for themselves and realise that they have been a source of enlightenment for others like them to come forward and make a difference in our today, for our tomorrow.

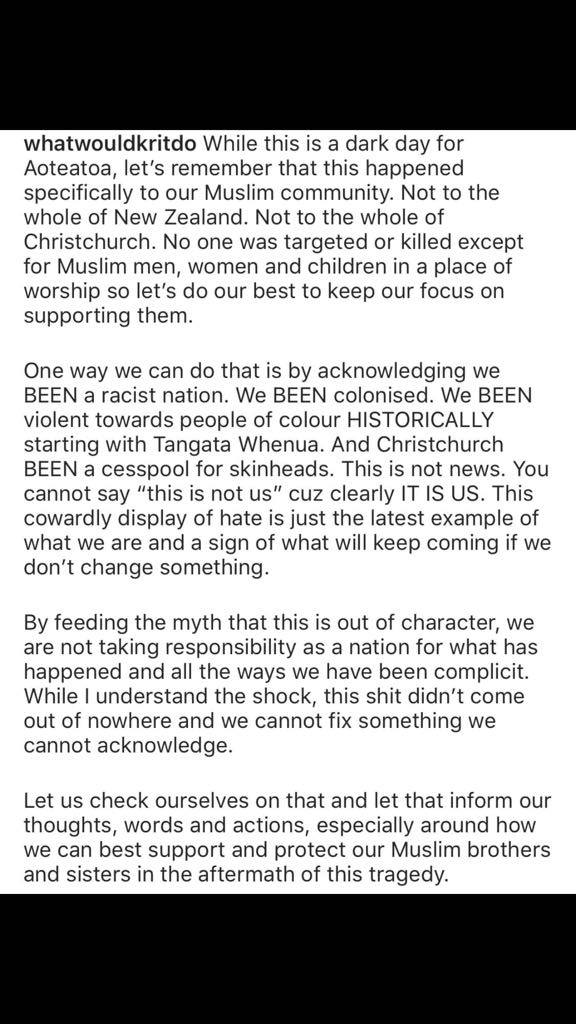

Above: a screenshot of a post shared on facebook that speaks volumes about what our country fails to see. Credit: https://www.facebook.com/whatwouldkritdo/

It’s a great power that sits in front us now. That power to unravel, acknowledge and heal. That power to forgive, as we know we have the capacity for, as we know our Muslim brother’s and sister’s are trying to do. A great power indeed. How do we move forward? How do we stomp out hate and bigotry, especially in the culture that we have been ignored in for generations? How? Tell me? Because I still hear people talking about Bastion Point, about Pukehinahina, about Wairau, about Parihaka, about racial profiling in stores, about adopting nicknames to suit the listener/teacher/employee/whānau. I still hear our kids in class telling a room full of strangers that she was bullied for being dark at school and this girl is only 19/20 years old, and the shame and hurt still resonates with me, who used to janola and sandsoap her skin raw in the 80’s to bleach the brown out so I wouldn’t be called ‘Dark Moon, full Moon, nigger, monkey, coon, shoe shine, dubbin, paint, lily (which are white, and therefore the opposite of what I am … quite clever actually), mud-pie, matchstick, skiddy’ – all of those pretty little names that stay with you and come back to the surface, all of those collective and generational memories you’re told by your kuia and kaumatua as a child when they recollect their childhood during the Native School years, when they tell their tupuna … YOUR tupuna narratives, all of that comes flooding back at once as trauma, when something like this, a terrorist attack on innocent people in our country, happens.

This country … New Zealand, Aotearoa, “Godzone”, needs to be reminded it where it’s roots comes from. Our future narrative starts with acknowledging that we need to be seen as the culture we have always been. Colonial trauma can only be healed when that process starts. Until then, our country will always hide behind closed curtains, or under the blanket where it feels cosy.

Above: a photo of a print I bought a couple of years ago in UAE by Nihad Nadam, titled “Ennakum Lan”. On the back, a translation: “You can only win people’s hearts with morals”.

Above: a photo of a print I bought a couple of years ago in UAE by Nihad Nadam, titled “Ennakum Lan”. On the back, a translation: “You can only win people’s hearts with morals”.

Above: Ngā Wai o Horotiu Marae

Above: Ngā Wai o Horotiu Marae